(Special issue on "Confronting militarism: Transitioning from the ways of war to peace.")

| Peace Monuments Confront Militarism |

"I thought we had quite enough memorials that seemed to revive the war spirit rather than to consider peace, which is, after all, the aim and end of every great struggle." -- Sculptor Adrian Jones as he prepared to cast the symbolic figure of "Peace" for the Uxbridge war memorial in 1924. As quoted by Gough (2003).

Militaristic and pacifistic values compete in many different ways, both intentionally and unintentionally, but no where more openly than in the public arena where both sides construct physical memorials (monuments) to display their values for present and future generations. Our cities are filled with the physical evidence of past efforts to interpret war and peace. Our newspapers are filled with completing proposals for using our public spaces to perpetuate various group's militaristic and pacifistic values into the future.

It is frequently observed (e.g. Bennett 1999, Knox 2009) that war monuments vastly outnumber peace monuments and that their ubiquity subliminally reinforces a pervasive culture of violence, at least in the United States. This is true in part because war monuments usually stand out by depicting guns and weapons, generals on horseback, and the frequent use of the very word WAR.

Symbols such as a dove, a laurel wreath, or the female form make some peace monuments equally easy to recognize. But others, such as the statues of statesmen who avoided war, of scientists who cured disease, and of civil rights martyrs who practiced non-violence, are not so readily identified as representing one of the many meanings of the word "peace."

But they do exist. Here is a small sample of ten peace monuments which confront militarism directly [Right click any image to enlarge]:

-- There are peace monuments made out of old weapons in many cities.1 Perhaps the oldest is the Charrure de la Paix (Plow of Peace) at the city hall in Geneva, Switzerland, where the First Geneva Convention was signed in 1864 and where the first international arbitration settled the Alabama Claims in 1872. This life-size agricultural implement is said to have been made from swords turned in by American army officers during a conference of the Universal Peace Union in Philadelphia, also in 1872.

-- The end of "the war to end all wars" inspired a lot of peace monuments, often call "peace memorials" in Commonwealth countries, e.g. "Peace Memorial Hall in Hertfordshire, England.2 According to the Peace Pledge Union (and Gough), this was to reflect the concept that "Peace" is the consequence of the victorious conclusion of "War." Since then, the word "peace" has gradually acquired broader and broader meanings.

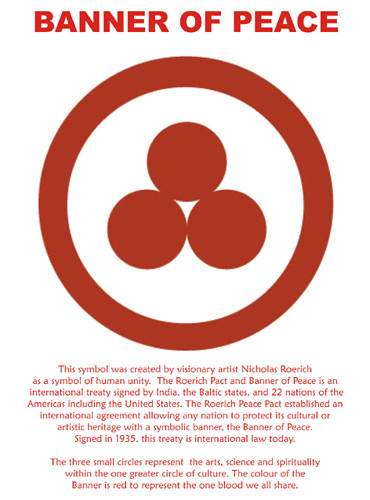

-- Russian artist and humanitarian Nicholas Roerich invented the "Banner of Peace" to protect monuments of cultural and historic importance during wartime. The "Roerich Pact" was signed in 1935 by 21 nations of the Americas at the White House in the presence of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt (and later by other countries). Alas, Roerich's eftorts are unappreciated today, except at Roerich museums in New York City and Moscow

.jpg)

-- In 1936 and 1938, suffragist and sometime communist Sylvia Pankhurst in London and college president Hamilton Holt in Winter Park, Florida, erected remarkably similar monuments depicting World War I bombs to express horror at mass killing, particularly of civilians. Holt's monument reads, "Pause, passer by, and hang your head in shame," then goes on to berate the inventor, the manufacturer, the statesman, the soldier, and the citizen for the use of such weapons.

-- The most famous anti-war monument of all -- Pablo Picasso's "Guernica" -- was commissioned by the government of Spain for the Paris International Exposition of 1937. The original painting is now in Madrid, and a full-size tapestry reproduction hangs outside the Security Council at the United Nations in New York City. On February 5, 2003, Guernica's anti-war message was covered over when secretary of state Colin Powell visited the UN to "prove" the existence of weapons of mass destruction in Iraq.

-- Hiroshima probably has the world's biggest concentration of peace monuments. Its very first was dedicated in 1948 to victims of the atomic bomb at Hiroshima Girls High School. Allegedly because the occupying US Army would not permit a direct reference to the bomb, the monument is inscribed "E=MC2."

-- One of the most audacious and eccentric clusters of anti-war monuments was created by surplus store owner Ed Grothus on private property in Los Alamos, New Mexico. In addition to a memorial to Joseph Rotblat (the only scientist to defect from the Manhattan Project), the cluster contains broken bombs, a mock church -- "Critical Mass Every Sunday" -- and the mantra "No one is secure unless everyone is secure."

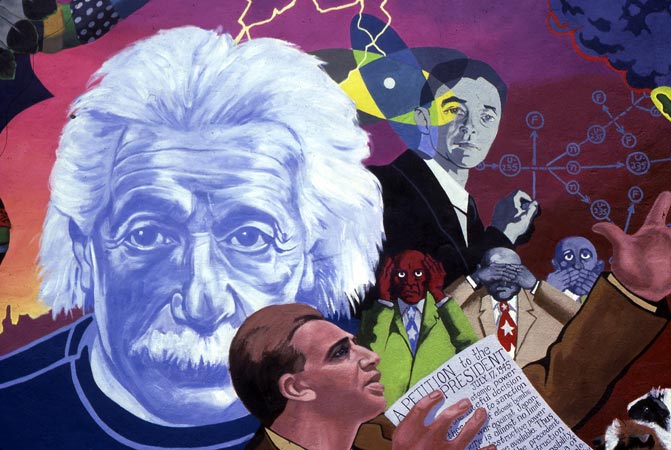

-- In 1985, Massachusetts muralist David Fichter painted a 60-foot wall in Atlanta, Georgia, during a cultural festival for nuclear disarmament. Entitled "Three Minutes to Midnight," the mural depicts nuclear scientist Leó Szilárd (who petitioned for the bomb not to be used on human beings), the Hiroshima Maidens, and local hero Martin Luther King, Jr., among many other personsifications of anti-nuclear peace activism.

-- In 1991, a dark mushroom cloud was erected outside the Civic Center in Santa Monica, California. Made from a massive black chain and named "Chain Reaction," the monument was designed by Los Angeles cartoonist Paul Francis Conrad. A plaque on the monument reads, "This is a staement of peace. May it never become an epitaph." In 2003, Conrad drew the same mushroom cloud above the words of Condoleezza Rice: "We don't want to be the smoking gun to a mushroom cloud."

There are at least a thousand other peace monuments in the United States and Canada. To find one near you, go to http://www.PeacePartnersIntl.org, click Peace Monuments Worldwide, and then choose the name of your state or province (or the name of any foreign country).

One way to help change our culture of violence to a culture of peace would be to identify local peace monuments, lead pilgrimages to distant peace monuments, and help the general public become aware of their existence and meaning.

1 There are peace monuments made from old weapons in at least the following sixteen cities: Beirut (Lebanon), Bogota (Columbia), Dessau (Germany), Geneva Switerland), Gulu (Uganda), Indianapolis (USA), Managua (Nicaragua), Maputo (Mozambique), Miami (USA), Rio Grande do Sul (Brazil), San Jose (Costa Rica), Seattle (USA), Timbuktu (Mali), Tirana (Albania), and Washington, DC (USA). return

2 "Peace memorials" were constructed after World War I in Australia, Canada, the Cayman Islands, England, St. Vincent, New Zealand, and Zanzibar -- but not in the United States. After World War II, the phrase became the generic name in English of many monuments, parks, and museums in Japan, notably in Hiroshima. return

|

|

| |

| |

| |

|