"The bell [in Oak Ridge] will survive long after all the participants in the Manhattan project and the objectors to ‘apologizing’ to Japan have been forgotten. What will remain is this symbol. I hope it will become a shrine for the many visitors who, by their pilgrimage to the Friendship Bell, will be participating in the sanctification of Hiroshima and the permanence of the tradition of non-use [of nuclear weapons]."

Alvin M. Weinberg, "The First Nuclear Era:

The Life and Times of a Technological Fixer [autobiography],”

American Institute of Physics, New York, 1994, page 270.

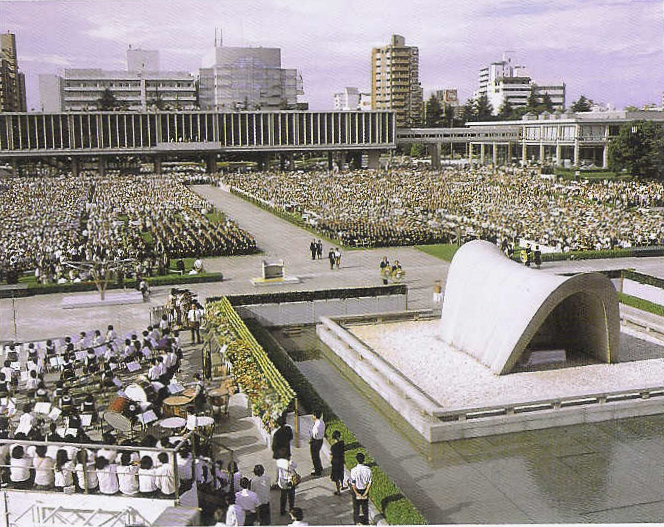

Hiroshima Japan 1964 |

|

He described his visit this way: "Visitors ring the bell [by] banging it with a 10-foot, horizontal wooden pole that is suspended by ropes. The day we were there [in 1991], perhaps 5,000 visitors were at the park, and the deep reverberations of the bell could be heard whenever a visitor had the courage -- and strength -- to hit the bell with the clapper pole. I took my turn, but I fear my sound was a bit puny compared with the sounds produced by some of the younger visitors. I was told by my hosts that the [park] attracts some 100,000 visitors from all over the world on each Aug. 6 -- that Hiroshima becomes a sort of shrine (perhaps like Bethlehem or Mecca) on the anniversary of the great killing. And even on an ordinary day, the whole place has a sort of religious feel. There are thousands of paper birds left by the many visitors, just as at other Japanese shrines. People walk about quietly and they talk in subdued tones -- especially when they stand before the mound that marks the mass grave of 10,000 victims. Could it be that the awful event of Aug. 6, 1945, is in fact being transformed into a religious event? Is Hiroshima becoming sanctified?"

It's as if Weinberg had lived seventy-six years for this very moment. His scientific career, his decades as director of America's largest scientific laboratory, and his policy making roles in and out of government were behind him. He already knew about the monuments and museums of Hiroshima. He already knew about the Peace Bell. Yet actually seeing it up close would would be life changing. Hiroshima caused Weinberg to think about his Past, to contemplate his Future, and to embark on a new venture which would consume the remainder of his life.

The "nagging question of Hiroshima" had never been far from the consciousness of Dr. Alvin M. Weinberg [1915-2006]. As a scientist of the secret Manhattan Project, first in Chicago, then in Oak Ridge, Tennessee, he helped make the bombs which destroyed Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945. Just before the bombs were dropped, he sympathized with the Franck report (in which scientists had recommended demonstrating the bomb before using it on Japan), and he signed the Szilárd petition (which urged President Truman to warn Japan before using the bomb to kill human beings). Later, like many others, he "came to the simple-minded view" that Hiroshima was justified because it ended World War-II.

But Weinberg always thought in sweeping terms about time and space. In 1961, he coined the famous phrase "Big Science" by comparing the scientific monuments of the twentieth century to the religious monuments of the Middle Ages. He wrote in Science:

"When history looks at the 20th century, she will see science and technology as its theme; she will find in the monuments of Big Science -- the huge rockets, the high-energy accelerators, the high-flux research reactors -- symbols of our time just as surely as she finds in Notre Dame a symbol of the Middle Ages... We build our monuments in the name of scientific truth, they built theirs in the name of religious truth; we use our Big Science to add to our country's prestige, they used their churches for their cities' prestige; we build to placate what ex-President Eisenhower suggested could become a dominant scientific caste, they built to please the priests of Isis and Osiris."

Later in the 1960's, Professor Thomas C. Schelling got Weinberg's attention by popularizing the concept of a "tradition of non-use of nuclear weapons." No nukes had been exchanged during the Korean War or during the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962. In the 1980's, the Soviet Union did not use them during the conflict in Aghanistan. By 1985, the world had gone forty years without the use of a single nuclear weapon. Up until then, military strategists assumed, as they always had, that any new weapon would become commonplace. But gradually it seemed that a taboo against the use of nuclear weapons had taken hold, and that every state with a nuclear option was loath to become the first to break the taboo, lest it unleash unprecedented and unpredictable consequences of unimaginable horror.

Weinberg realized that such a taboo offered hope, both as a way for him to resolve his own "nagging question" and for the world to cope with the most perplexing question not only of the twentieth century but for centuries to come. He discussed both aspects with William Pollard, another Manhattan Project scientist who was also an Episcopal priest. Pollard told Weinberg about the writings of theologian and scholar Mircea Eliade and sent the following thoughts to Weinberg in a letter:

"Eliade has made a distinction between a people's 'profane time' and its 'sacred time." In sacred time, historical deeds and events gradually come to partake of the permanence of myth, while in profane time they gradually lose their grip on people and bcome merely historical material for historians, i.e. they remain in historical time. Is this the destiny of Hiroshima: to become a universal myth deeply grounded in the sacred time of all the peoples on earth, the symbol of their conviction that nuclear warfare must never be allowed to occur?"

Weinberg liked this idea but appeared to be unsure if the atomic bombing of Hiroshima occured during "profane time" or "sacred time." He later reasoned that the "extraordinary singularity" and vast suffering of Hiroshima could define a religious instant, thus qualifying Hiroshima to become part of humankind's religious tradition, even if the times were "profane."

In late 1985, the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists invited Weinberg to publish his impressions of the fortieth anniversary of the Hiroshima bomb. Weinberg wrote that he still believed that the bombing of Hiroshima (but not Nagasaki) had been necessary to end the war. But now he had a second, far more important reason to favor the use of the Hiroshima bomb. Anticipating his visit to Hiroshima by six years, he observed that the fortieth anniversary in August 1985 had seen an outpouring of emotion, a display of concern, that goes much beyond any previous observation of the Hiroshima bombing. "Are we witnessing a gradual sanctification of Hiroshima," he asked the readers of the bulletin. "Is Hiroshima being elevated to the status of a profoundly mystical event, an event untimately of the same religious force as the crucifixion, the Holocaust, or the Hegira." Similar to the Ten Commandments or Islamic dietary laws?

In 1988, McGeorge Bundy published "Danger and Survival: Choices About the Bomb in the First Fifty Years," providing Weinberg with historical evidence of the Cuban Missile Crisis and other nuclear standoffs, evidence which supported Schelling's thinking about the "tradition of the non-use of nuclear weapons."

By the time he visited Hiroshima, Weinberg had already concluded that "the sanctification of Hiroshima answers my nagging concern. Was Hiroshima necessary? Yes, I now say, not only because it ended World War II, but because it was the unique, horrible event that may make the tradition of non-use permanent. The sanctions and taboos surrounding nuclear weapons 100 or 1,000 or 10,000 years from now, religious in character, will have started with the awful event of August 6, 1945."

In 1991, Alvin Weinberg was the most renowned, honored, and beloved citizen of Oak Ridge. He had directed the Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL) from 1955 until 1974 and the Institute for Energy Analysis (IEA) until 1985. Retirement had not slowed his life-long pursuit of scientific and spiritual truth. In 1991, he visited Hiroshima and Nagasaki to "review with our Japanese counterparts at the Radiation Effects Research Foundation (RERF) the epidemiological studies of the 150,000 survivors of the two atomic bombs on Japan."

As he rang the Peace Bell and stood before the burial mound, Weinberg must have also been thinking about events in Oak Ridge, his home since 1944 and the city which, with Weinberg's help, had enriched the uranium that destroyed Hiroshima in 1945. He would have known that an international couple (Indian mathematician at ORNL and his Japanese wife) had proposed to bring a large, four-ton bronze Japanese temple bell to Oak Ridge as a symbol of peace and international friendship. He would also have known that the Oak Ridge Community Foundation (ORCF) had chosen this "International Friendship Bell" to be the "suitable memorial" of the city's fiftieth anniversary celebration in 1992-1993.

Weinberg also knew that neither the bell's proponents nor the ORCF had been able to raise sufficient funds to pay for the bell and that it was therefore not likely to be ready in time for the anniversary celebration. Just before leaving for Hiroshima, he probably had heard the first rumblings of some war veterans and other Oak Ridge citizens who thought the bell might be considered an apology to Japan for Oak Ridge's role in World War II, and of others who were beginning to complain that the bell's identification with the war would eclipse the city's long history of providing uranium for Cold War weapons, for the development of atomic power and medical isotopes, and for many other scientific achievements.

As he listened to the bell in Hiroshima and thought about Hiroshima's sancification in support of the taboo against the use of nuclear weapons (then forty-six years and counting), Weinberg had an epiphany: Bronze bells in Hiroshima and Oak Ridge would forever link the ciies of cause and tragic effect. Both cities needed to be sanctified. Their two bells would last for hundreds of years and jointly remind visitors for centuries to come about the tragedy of nuclear weapons and the importance of preserving the tradition of non-use.

But the Oak Ridge bell was in trouble, and Weinberg had had absolutely no role in its promotion. As he walked around Peace Memorial Park, Weinberg decided that the time had come for him to intervene. This was a decision which would preoccupy him for the rest of his life.

A few days after Weinberg returned home in October 1991, an ORCF press release announced that he would become honorary chairman of the bell committee. Three days later, the Oak Ridger newspaper published a guest column entitled "Friendship Bell could be an important symbol here,” in which Weinberg said in part:

"We in Oak Ridge are justifiably proud of the role we have played in keeping the peace, but the knowledge of making bombs will never die. We must contemplate a world 50, 100, 1,000 years from now that will live with the knowledge. How can we guarantee that the hydrogen bombs like the ones we make in Oak Ridge won’t be used during all those years? I suggest...that mankind must surround the use of nuclear bombs with taboos that are of such strength, such depth, such force as to make the use or even illicit possession of nuclear weapons a heinous crime against humanity, punishable by death. To establish taboos of such power that last over millennia means that somehow these taboos must acquire religious significance, for only religious happenings remain in humanity’s consciousness for millennia. Terrible historical events, occurring at the right time, do acquire a religious symbolism -- for example, the crucifixion, or much more recently, the Jewish Holocaust, which is now observed in Jewish liturgy...

“Oak Ridge as well as Hiroshima should be sanctified. We produced the uranium-235 that went into the Hiroshima bomb. I now believe the use of the bomb at Hiroshima was justified both because it ended the war, and because it made August 6, 1945, a day that history and religion will never forget. I therefore think it is very appropriate that the shrine that exists at Hiroshima where the bomb was used be replicated at Oak Ridge. The Oak Ridge Friendship Bell ought to acquire the same kind of transcendent, religious character as has the Hiroshima Bell. It will forever symbolize Oak Ridge’s recognition that the nuclear holocaust at Hiroshima should never be repeated."

Whether Weinberg approached the bell's promoters or they approached him is unclear, but they needed each other. The promoters needed Weinberg’s prestige and worldwide connections to energize the bell project, and Weinberg needed the bell as a way to link Oak Ridge and the Manhattan Project to the sanctification of Hiroshima. This partnership would eventually assure the successful completion of the bell project, but not for some time yet to come.

Weinberg’s participation did not immediately rescue the bell project. By January 1992, very little money had been raised for the bell, the anniversary celebration was fast approaching, and the ORCF executive committee recommended that the foundation cancel the entire bell project. Alvin Weinberg and his wife Gene were vacationing in Mexico, and the chair of the bell committee passionately appealed to the ORCF board to postpone making a decision until Weinberg could be present to defend the project in person.

In March, Weinberg began focusing his own time to raise money for the bell from professional contacts all over the world. On April 14, a check for $14,008.05 arrived from Japanese sister city Naka-Machi. When the ORCF board met on April 30, Weinberg was at last able to show some progress. The board decided to retain the bell as an unfunded foundation project -- but to separate it from the anniversary celebration.

On September 18, 1992, the ORCF launched an ambitious series of anniversary events which continued through December 1993. By all accounts, the celebration was immensely successful. But there were also negative outcomes: The ORCF faded into obscurity despite the intention of its founders that it become a permanent institution, and there was still no “suitable memorial” to mark Oak Ridge’s first five decades.

In April 1993, the Japanese bell maker visited Oak Ridge, forcing the bell committee and ORCF to dig as deeply as possible in their pockets. The bell maker offered a $42,000 “discount,” thus reducing the total cost of the bell to $83,000 (FOB his foundry in Kyoto). By this time, the bell committee had bank deposits of only $60,000 but promised to commit all future donations. To make it possible for the contract to be signed, Weinberg pledged $10,000 of his own money which he raised by selling his three personal gold medals: The Atoms for Peace Award (1960), the Heinrich Hertz Memorial Award (1980), and the Enrico Fermi Award (1980).

Weinberg stayed home when Oak Ridge's mayor and sixteen other Tennesseans gathered in Kyoto for the bell’s casting on July 14, 1993: Another former director of ORNL photographed and video-taped the casting. The video shows employees in khaki uniforms and yellow hardhats performing dangerous tasks while an orange-robed Shinto priest and his assistant face cauldrons of molten metal, chant, and throw in what appear to be slips of paper. The Indian and Japanese couple from Oak Ridge is seen adding what appear to be a few dogwood branches from Tennessee.

The next day, the Tennesseans took the train to Hiroshima and visited Peace Memorial Park. Mayor Ed Nephew laid a wreath and was followed everywhere by reporters who were keenly aware of the connection between Oak Ridge and the Hiroshima bomb. Later, a former Fulbright exchange student offered to crate the bell, and the Honda Motor Car Company agreed to ship it on a car carrier to the port of Savannah, Georgia.

The project languished without funds for another two years and suffered a political setback when Ed Nephew and two other supporters on the city council were defeated by newcomers who cared little for the bell but were very sensitive to the chorus of citizens who criticized it for any number of reasons.

In June 1995, the Rev. Dwyn M. Mounger was called from Anderson, South Carolina, to become pastor of the First Presbyterian Church. The son of a Mississippi civil rights and peace activist, Mounger was acutely aware that, within less than six weeks of his arrival, the world would observe the fiftieth anniversaries of Hiroshima and Nagasaki on August 6 and 9, 1995.

Mounger’s solution to this dilemma was to compose a “Litany of Remembrance” for the victims of all wars, up to and including the victims of the recent bombing in Oklahoma City. Mounger soon learned about the bell and acquired a miniature to ring in conjunction with the litany during his Hiroshima Day service. Parishioners also introduced Rev. Mounger to Dr. Weinberg.

The Manhattan Project scientist and the newly arrived minister hit it off immediately. Mounger wrote another Presbyterian minister on August 1 that Weinberg “is one of the most inspiring people I’ve ever encountered. [He] sees Hiroshima and August 6, 1945, as a ‘religious event’ (in the same sense as was the Holocaust) which has the potential of forever making any further use of nuclear weapons a universal taboo.” In November, Weinberg and Mounger outlined a book which they intended to co-author on the sanctification of Hiroshima.

Construction of a pavilion to house the bell became possible when a check for $23,121.48 arrived unexpectedly from 571 individual and corporate members of the Atomic Energy Society of Japan. Political support was obtained when another retired Manhattan Project scientist composed a "statement of purpose" which interpreted the bell as representing just about everything that had happened during Oak Ridge's first fifty years. (The self-appointed author said he suffered in silence for five years but finally realized what troubled him. Weinberg and other bell proponents were trying to rewrite Oak Ridge history. Their emphasis on “Manhattan Project workers” and the four dates cast into the bell -- Pearl Harbor, Hiroshima, Nagasaki, and VJ-Day -- suggested that Oak Ridge’s only service had been to enrich uranium during World War II and to bomb Japan, whereas Oak Ridge had actually made many positive contributions over its entire fifty years. Rev. Mounger persuaded Dr Weinberg to accept the official "statement of purpose," but, of course, the bell would continue to be seen through the eye of the beholder, and, to Weinberg's eye, the Oak Ridge bell will forever evoke the santification of Hiroshima.

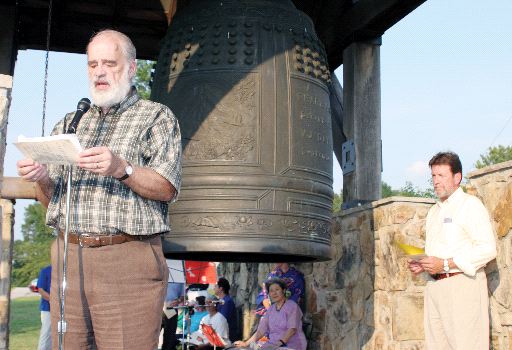

Friendship Bell Oak Ridge U.S.A. 1996 |

|

On March 4, 1996, the bell was trucked from the municipal building to the incomplete pavilion in A.K. Bissell Park and lifted into place. Its dedication took place on May 3. Dr. Sigvard Eklund, Director General Emeritus of the International Atomic Energy Agency, was the keynote speaker; and Rev. Mounger delivered the invocation. The chairman of ORCF formally presented the bell to the newly elected mayor who (reluctantly) accepted it on behalf of the city. At that evening's banquet, addresses were made by former Senator Howard Baker, Jr. (later to be American Ambassador to Japan) and by Keiji Naito, professor of physics and president of the Atomic Energy Society of Japan.

On the following day, May 4, Dr. Weinberg achieved an intellectual tour-de-force with a world-class symposium devoted to “Strengthening the Tradition of Non-Use of Nuclear Weapons.” The first paper was by Prof. Thomas Schelling (who would win a Nobel Prize in 2005 for his work on game theory and deliver his acceptance speech about the tradition of non-use), and the last was “The Bell and the Bomb” by Dr. Alvin Weinberg

The Oak Ridge bell now stands proudly in its cantilevered pavilion combining features from Asian and Western traditions. As in Hiroshima, the bell can be rung by anyone at any time – sometimes frivolously and sometimes solemnly. It is probably fair to say that most Oak Ridgers now accept the bell, respect its unique history, and value it as a permanent addition to their civic landscape.

Dr. Alvin Weinberg realized his dream. The Oak Ridge bell and the Hiroshima bell will outlive everyone alive today. In 50, 100, 1,000 years, there will be those who say, "Surely these bells were intended to perpetuate the tradition of the non-use of nuclear weapons." They will know then if the tradition has succeeded. It's not yet for us to know. But, so far, with the help of the two bells, and with the sanctification of Hiroshima which the two bells represent, the tradition yet endures.

(in wheelchair) on 60th Anniversary of the Non-use of Nuclear Weapons Aug. 9, 2005 |

|

for Alvin Weinberg Pollard Auditorium Oct. 18, 2006 |

|

Barkenbus, Jack N., ed. by (1992, January ), "Ethics, Nuclear Deterrence, and War," Professors World Peace Academy, New York, pp. 350.

Barkenbus, Jack N., & David L. Feldman, ed. by (1996, August), "Strengthening the Tradition of Non-use of Nuclear Weapons," Energy, Environment and Resources Center (EERC), University of Tennessee, Knoxville, pp. 69. Contains 11 papers from a symposium of the same name held in Oak Ridge, Tennessee, May 4, 1996, in connection with the dedication of the International Friendship Bell on May 3, 1996. The 11 papers are by

Senator Howard H. Baker, Jr.,

Dr. Alvin M. Weinberg,

Prof. Thomas C. Schelling,

Prof. Bruce Russett,

Prof. Freeman J. Dyson,

Dr. Jack N. Barkenbus,

Prof. Sidney D. Drell,

Dr. David H. Fischer,

Admiral Stansfield Turner, and

Prof. Frederick Seitz.

Copy in possession of the author.

.

Bundy, MGeorge (1988), "Danger and Survival: Choices About the Bomb in the First Fifty Years," Vintage Books, New York, pp. 735.

Kawata, Tomio (1996, June 6), “Guest Column: Japanese visitor shares his essay on the [International Friendship] bell,” Oak Ridger newspaper, Oak Ridge, Tennessee. NB: Kawata attended the bell dedication on May 3, 1996, and afterwards mailed this text to Rev. Dwyn Mounger from Japan.

Levering, Miriam Lindsey (1999, January 4), "Oak Ridge Bell Report," pp. 24, unpublished. Refutations of allegations by plaintiff in the case of Robert Brooks vs. the City of Oak Ridge. Expert testimony prepared for and submitted to the city's counsel but not used in court. Copy obtained from the author.

Levering, Miriam Lindsey (2000, August 7), “In the Atomic City, for whom does the temple bell toll?,” paper delivered to the XVIII International Congress, International Association for the History of Religion, Durban, South Africa, unpublished.

Levering, Miriam Lindsey (2003, Fall), "Are friendship bonsho bells Buddhist symbols?: The case of Oak Ridge [Tennessee]," Pacific World (Journal of the Institute of Buddhist Studies), San Francisco. 3rd series, no. 5, pp. 163-178. NB: Despite its date, this journal did not appear until Fall 2004, and the article contains information dated in early 2004. Full text is on-line.

Levering, Miriam Lindsey (2005 November/December), “Remembering Hiroshima in Oak Ridge, Tennessee,” Dharma World, Kosei Publishing Co., Tokyo, pp. 6-11.

Lollis, Edward W. (July 17, 2005), "The Oak Ridge International Friendship Bell," Conference on The Atomic Bomb and American Society, Center for the Study of War and Society, University of Tennessee, Oak Ridge (Tennessee). One of 18 papers published in Mariner, Rosemary B., & G. Kurt Piehler, ed. by (2009), "The atomic bomb and American society: New perspectives," University of Tennessee Press, Knoxville, pp 344-380. Full text is on-line. Click here for pictoral version.

Lollis, Edward W. (2008 & ongoing), "Peace monuments around the world," web site (http://peace.maripo.com) with about 200 individual web pages. Contains photos & interactive links to hundreds of peace monuments. Monuments are arranged thematically, geographically, chronologically & by physical form. This web site is owned & maintained by the author. Click here for home page.

Lollis, Edward W. (2008 & ongoing), "Peace monuments in Hiroshima (Japan)," web site (http://peace.maripo.com/x_japan_hiroshima.htm).

Lollis, Edward W. (2008 & ongoing), "Peace monuments in Tennessee & Kentucky (USA)," web site (http://peace.maripo.com/x_us_tn.htm).

Mounger, Rev Dwyn M. (1995, August 6), "Litany of Remembrance," First Presbyterian Church, Oak Ridge, Tennessee. Presented on 50th anniversary of the Hiroshima bomb. Text published by Oak Ridger newspaper and elsewhere. Click here for an on-line article about the litany.

Pals, Daniel L. (1996), "Seven Theories of Religion," Oxford University Press, pp. 304. Introduces a sequence of seven "classic" attempts to explain religion by E.B. Tylor and James Frazer, Sigmund Freud, Emile Durkheim, Karl Marx, Mircea Eliade, E.E. Evans-Pritchard, and Clifford Geertz. N.B. This book impressed Alvin Weinberg.

Paul, T. V. (1995, December), "Nuclear Taboo and War Initiation in Regional Conflicts," Journal of Conflict Resolution, Sage Publications, voume 39, number 4, pp. 696-717.

Paul, T. V. (2009), "The Tradition of Non-Use of Nuclear Weapons," Stanford University Press, Stanford., pp. 336.

Schelling, Thomas C. (Summer 2000), "The Legacy of Hiroshima: A Half Century Without Nuclear War," Institute for Philosophy & Public Policy, Maryland School of Public Affairs, University of Maryland, College Park, Maryland, volume 2, number 3, pp. 7. Copy in possession of the author. An earlier version of this article appeared in The Key Reporter (quarterly publication of the Phi Beta Kappa Society), volume 65, number 3 (Spring 2000).

Schelling, Thomas C. (2006), "An Astonishing Sixty Years: The Legacy of Hiroshima," American Economic Association. Revised version of a paper read in Stockholm, Sweden, on December 8, 2005, when Schelling received the "Bank of Sweden Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel."

Tannenwald, Nina (2005, Spring), "Stigmatizing the Bomb: Origins of the Nuclear Taboo," International Security, MIT Press Journals, volume 29, number 4, pp. 5-49.

Weinberg, Alvin M. (1985, December), "The Sanctification of Hiroshima," Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, Chicago, volume 41, number 11, p. 34. See full text below.

Weinberg, Alvin M. (1988, November), "Deterrence, defense, and the sanctification of Hiroshima," paper presented at the 17th Internationl Conference on the Unity of the Sciences, Los Angeles, California. Published as article #16188 in "The World and I," Washington, DC, June 1989, pp. 467-491. Reprinted in "Nuclear Reactions: Science and Trans-Science," American Institute of Physics, 1992, p. 115.

Weinberg, Alvin M. (1991, October 18), "Guest Column: Friendship Bell could be an important symbol here," Oak Ridger newspaper, Oak Ridge, Tennessee.

Weinberg, Alvin M. (1993, October 4), "A [personal] statement on the Friendship Bell," delivered to the Oak Ridge City Council, unpublished. Copy in possession of the author.

Weinberg, Alvin M. (1994), "The first nuclear era: The life and times of a technological fixer [autobiography]," American Institute of Physics, New York, pp. 291. Includes sections entitled "Sanctification of Hiroshima" and "The International Friendship Bell." See book review by Mike Moore in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, vol. 52, no. 1 (January/February 1996).

Weinberg, Alvin M., & Rev. Dwyn Mounger (1995, Nov. 16), "The Sanctification of Hiroshima," outline of a proposed book to be written by the two collaborators, pp. 2, unpublished. Copies obtained from both authors.

Weinberg, Alvin M. (1996, May 4), "The Bell and the Bomb," paper delivered to symposium on "Strengthening the Tradition of Non-use of Nuclear Weapons" at Oak Ridge Associated Universities (ORAU). Published in Barkenbus & Feldman (1996, August). (This symposium was organized by Dr. Weinberg and took place the day after the dedication of the International Friendship Bell on October 3, 1996.)

Weinberg, Alvin M. (1997, March 27), "Scientific Millenarianism," Rustum Roy Lecture, American Ceramic Society, pp. 7. Discusses four catastrophes: Bolide Impact, carbon dioxide warming, improper waste disposal, and thermonuclear war, including the "sacralization, even sanctification, of Hiroshima." Copy in possession of the author.

Weinberg, Alvin M. (1997), "The Bell and the Bomb," Cosmos Journal, Cosmos Club, Washington, DC. Similar to Weinberg (1996, May 4) but shorter. Full text is on-line.

Wikipedia, Mircea Eliade (1907 – 1986).

Wikipedia, William G. Pollard (1911–1989).

Wikipedia, Thomas Schelling (b.1921).

Wikipedia, Alvin M. Weinberg (1915 - 2006).

Wikipedia, Big Science.

Wikipedia, Manhattan Project.

Wikipedia, Sanctification.