From "The Peace Chronicle," newsletter of the Peace & Justice Studies Association (PJSA), Winter 2009-2010.

(Special issue on "Peace Education.")

Peace Monuments Assist Peace Education

By Edward W. Lollis A plain stone like this, standing on such memories, having no reference to utilities, but only to the grand instincts of the civil and moral man, mixes with surrounding nature -- by day with the changing seasons, by night the stars roll over it gladly -- becomes a sentiment, a poet, a prophet, an orator, to every townsman and passenger [sic], an altar where the noble youth shall in all time come to make his secret vows. -- Ralph Waldo Emerson, April 19, 1867

Emerson pronounced these words as he dedicated a Civil War monument in Concord, Massachusetts. His oratory is a bit flowery by today's standard, but he captured the essence of a public monument about as well as anyone before or since.

According to Emerson, a monument preserves memory. It becomes "a sentiment, a poet, a prophet, an orator" to every citizen and passerby. And an "altar" for ritual and ceremony in times to come.

In other words, monuments are both passive and active. They are time capsules from the past which permanently record the uncensored feelings of their creators and silently transmit those feelings for all time to come. Every monument is a history lesson.

Yet monuments also serve to reflect the values of contemporary visitors. They are symbolic objects onto which we project our own feelings and from which we receive inspiration to take action in today's world. And our children will in turn project the feelings of their time

Consider how our country's many war monuments have conditioned your students to accept a culture of war and violence. Now consider how peace monuments might help wean your students away from violence and toward the culture of peace you are trying to inculcate.

To illustrate what can be learned by visiting peace monuments, here are fifteen examples in various parts of the USA and Canada [Right click any image to enlarge]:

-- Monuments are physical and permanent. So are works of fine art. The Getty Center in Los Angeles displays "Mars and Venus: Allegory of Peace" [1770] by French painter Louis Jean François Lagrenée [1724-1805]. The peace symbolism of this painting is beautiful to behold: Nude lovers, a laid down sword, and a pair of nest building doves.

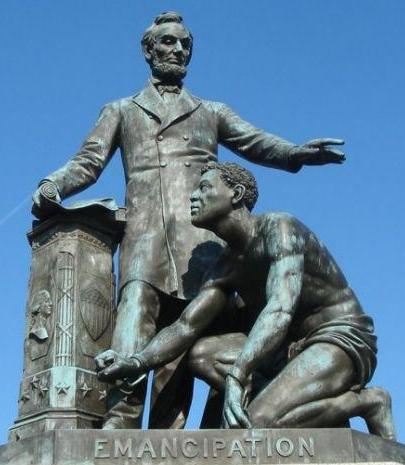

-- Emancipation of the slaves is a seminal event in the history of American peace and justice. Yet -- as pointed out by Prof. Kirk Savage -- the contemporary "Emancipation Memorial" [1876] on Capitol Hill in Washington, DC, shows Lincoln towering paternalistically over the kneeling figure of Archer Alexander [1828-1880?], the last slave captured under the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. (Note 1)

-- Peace activism is dramatically represented on Mount Rubidoux in Riverside, California, by the "Testimonial Peace Tower" [1925] for Frank Augustus Miller [1857-1935] who sought world peace and founded what is now the World Affairs Council of Inland Southern California. His tower bears the names and coats of arms of every nation of that time.

-- America celebrated the end of World War I by constructing the 148-foot "Great Frieze of War and Peace" [1926] overlooking the palatial new train station of Kansas City, Missouri. Man's "progress from war to peace" is triumphantly depicted by sculptor Edmond Amateis [1897-1981].

-- Twelve years later, FDR and elderly veterans from both sides lit the eternal flame of the "Peace Light Memorial" [1938] on the Gettysburg battlefield, thus symbolizing the ultimate reconciliation of North and South. The monument was seriously vandalized in January 2009.

-- On the eve of World War I, the Salt Lake City Council of Women laid out a series of International Peace Gardens [1940] in Jordan Park. Interrupted by years of war and neglect, twenty four peace gardens have been developed by local ethnic and national groups. In 2002, eighty-four peace poles were moved here from the site of the Winter Olympic Games.

--Hiroshima, Nagasaki, and United Nations headquarters in New York City host the world's three biggest concentrations of peace monuments. As noted by PJSA member Joyce Apsel, a tour of UN headquarters [1950] is ideal for peace education. One of the UN's many peace monuments is the "Golden Rule Mosaic" [1985] made by Venetian artists from the famous illustration by Norman Rockwell [1894-1978]. (Note 2)

-- Mary Dyer [c1611-1660] was hanged in May 1660 for refusing to abandon the principles of freedom of speech and conscience. Three hundred years later, Quakers celebrated her memory by erecting a Statue of Mary Dyer [1959] at the State House in Boston, and copies were placed outside the Friends Center in Philadelphia and on the campus of Earlham College in Richmond, Indiana.

-- In 1971, the City of Houston, Texas, turned down the "Broken Obelisk" of sculptor Barnett Newman [1905-1970] because it memorialized the recent martyrdom of Martin Luther King, Jr. [1929-1968] So art connoisseurs Dominique and John de Menil erected it front of their privately-financed "Rothko Chapel" [1971]. (The chapel contains "spiritual" paintings by Mark Rothko [1903-1970].)

-- Chicago, Los Angeles, and Philadelphia benefit from the social criticism of community murals. One example, "For a New World" [1973], on the side of Holy Covenant United Methodist Church in Chicago, depicts (1) political brutality, killing & repression. (2) the promise of a new world where all people live in peace, and (3) the admonition to dedicate our lives to justice through our daily work. (Note 3)

-- The US-Canadian border is dotted with peace monuments. The most imaginative is "SunSweep" [1985] by sculptor David Barr. Its three stones -- on the Atlantic in New Brunswick, on the Pacific in Washington state, and on an island in the Lake of the Woods -- are separated by 2,778 miles!

-- Peace heroes are celebrated at the "Pacifist Memorial" [1995] outside the "Peace Abbey" in Sherborn, Massachusetts. Six radiating brick walls containing the names of and quotations from famous pacifists surround a statue of Mahatma Gandhi.

-- Peace museums thrive in Europe and Japan, but the only surviving example in North America is the Dayton International Peace Museum [2005] in Dayton, Ohio. It includes exhibits on the Dayton Peace Accord [1995] and on the Nobel Peace Prize. (Note 4)

-- The only exhibit in North America telling the story of Hiroshima is "Stories of Hope" [2008] at the Peace Resource Center (PRC) on the campus of Wilmington College in Ohio. On August 1-7, 2010, the PRC will host the first "Peeacebuilding Peacelearning Intensive" of the new National Peace Academy (NPA).

-- Birthplace museums and other monuments to Nobel Peace Prize laureates are sprinkled across North America. The most recent is the 200-foot "Obama Nobel Peace Mural" unveiled at the private art gallery of Vietnamese refugee artist Huong in Miami, Florida, on December 10, 2009, the same day that President Obama accepted the prize in Oslo, Norway.

There are at least a thousand other peace monuments in the United States and Canada. To find one near you, go to http://www.PeacePartnersIntl.org and click the name of your state or province (or the name of any foreign country).

Suggest that your students look for and visit peace monuments. Their doing so will supplement what you are teaching them in the classroom. And -- little by little -- visiting peace monument will help bring about a culture of peace.

Endnotes:

(1) Savage, Kirk (1999), "Standing soldiers, kneeling slaves: Race, war, and monument in nineteenth-century America," Princeton University Press, Princeton.

(2) Apsel, Joyce (2008), "Peace & human rights education: The UN as a museum for peace," pp. 37-48, in Anzai, Ikuro, et al, ed. by (2008), "Museums for peace: Past, present and future," Organizing Committee, Sixth International Conference of Museums for Peace, Kyoto Museum for World Peace, Ritsumeikan University, Kyoto (Japan).

(3) Weber, John Pitman (1998), "Toward a People's Art: The Contemporary Mural Movement," University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque. First published in 1977.

(4) Abrams, Irwin (2001), "The Nobel Peace Prize and the Laureates: An Illustrated Biographical History 1901-2001," Science History Publications, pp. 350, with a forward by Kenneth Boulding. Irwin is Professor Emeritus at Antioch College and helped design the museum's exhibit.